S.T.A.L.K.E.R. – Escape from Reality

The first S.T.A.L.K.E.R. game was released in 2007, and it was a cultural phenomenon in post-Soviet countries for multiple reasons, some of which I will discuss in the context of the sequel here as well. Everybody in Ukraine has heard about Stalker, even if they have not played it. So, waiting for the sequel was something like waiting for Half-Life 2—everyone was very excited, and many didn't believe it would actually happen. However, it did, and despite all the hiccups, it is a good game, even though it still has a path ahead.

There are/will be plenty of articles and videos about the story and reviews of the game, and I am not a big master of these (even though I like to write some from time to time). What I want to talk about instead is sharing a few thoughts that have struck me while playing the game, getting my first ending, and watching other people's reviews and possible endings—how this game, from the core, is a reflection of the generational trauma and coping mechanisms of the nations trapped inside a cage that was called the Soviet Union. From a cultural perspective, rather than a political one.

GSC Gaming World

GSC Gaming World is a legendary Ukrainian game developer founded in 1995 in Kyiv by Sergiy Grygorovych at the age of 15, whose initials are the basis of the company name. They are mostly known for the development of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Cossacks games, although they have created many more titles. And they are one of the first video game companies in Ukraine. So it has a rich history.

At its peak, they had 200 employees, almost securing itself as a Ukrainian gaming powerhouse, until something went wrong in 2011, when they suddendly shut down, after a few years from the start of the first attempt to work on S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2 It was revived in 2014 with the brother of Sergiy, Evgeniy Grygorovych, taking the leadership as CEO. Then, they released another sequel to the Cossacks game and started working on S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2 from scratch in 2018.

Today, it seems they have up to 500 employees worldwide. With the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, they managed to move many of their crew from Ukraine to Prague in the Czech Republic and finished the game there. Some former employees have enlisted in the Ukrainian army, and some have already fallen while fighting for their country.

In 2024, Maksym Krippa became the owner of GSC Game World, a Ukrainian entrepreneur and investor known for his contributions to the development of esports and tech startups in Ukraine. While the company remains private and independent, it's barely an indie studio.

Context

I believe this is why this game became so big in Eastern Europe and became not just another hardcore survival shooter but a cultural phenomenon in Ukraine and beyond. For players in Western Europe and the Americas, it can be just an exotic flavour of the Soviet Union aesthetics shooter, something fresh and mysterious, as the perception of the totalitarian country is very different from within and outside. And that was intentional. The Soviet Union tried very hard to make itself appealing to the Western countries, to look not just better than it was, but conceptually different. To present an alternative, which it never was.

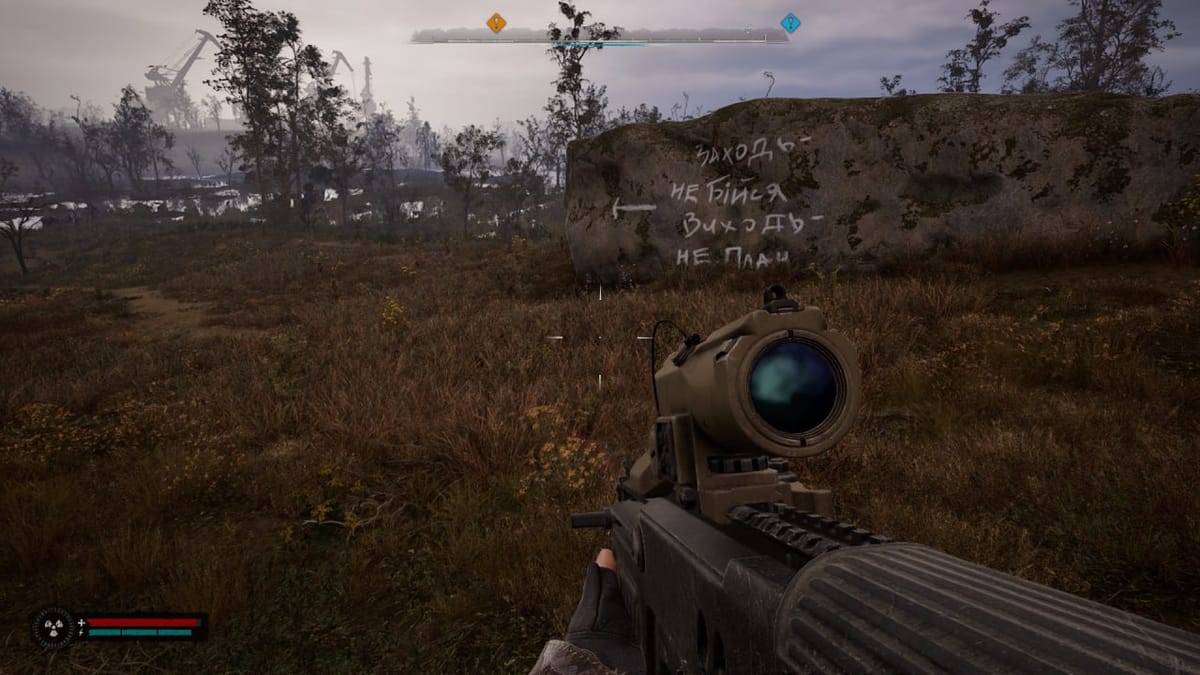

From within, it was quite literally a cage—a place you can never leave, a place you will never be free in, and a place you will never be able to change because it's so massive and so mixed up that you struggle to keep any identity, but a Soviet one. For any other, you will be persecuted and alienated. And a Soviet identity is about dissolving yourself in the masses, stopping being a person and becoming a small expandable bolt in the machinery of the Soviet Union. And these bolts also have their representation in the game – you never run out of them, and you throw them as trash into the abyss to be consumed by the power of anomaly.

Escape

So, what does it all have to do with the S.T.A.L.K.E.R.? The game presents us with the Zone–a result of terrible experiments, the exclusion zone. Just saying this aloud already gives me chills because of how allegorical it all sounds in the context of the Soviet Union itself. But the Zone is wild and untamable; the ones who created it can't take it under control–the supervisory board, which is a super Soviet thing to have, unnamed people with unlimited power outside the Zone. The Zone is dangerous and unpredictable; most who go there die. It has no laws or rules, no kings or general secretaries, but people go there nevertheless. Because the only thing they actually care for is... freedom. Freedom to be who you are, despite the risks. They see the escape. Perhaps, the only escape from the crushing pressure outside the Zone, which wants to dissolve your very nature, to force you into the line.

Alternative

And this is very different from what you see in the games from Western developers. What are the iconic games that appeared at a similar time there are about?

- Half-Life. The 1998 shooter is about another scientific experiment that goes wrong, but here, you fight an alien invasion. It continues in the sequel in 2004 with the alien occupation of the planet. Allusions to the Soviets, most probably, as the memory of the Cold War has not yet faded. But the idea here is to fight the distinctive enemy, "them".

- Doom. The 1993 game is about a marine sent on a suicide mission who fights through hordes of demons and aliens, ending up with another alien invasion of the planet Earth.

- Call of Duty. The infamous game, released in 2003, is all about the events of World War 2 and fighting the Nazi Germany. This is a very popular concept with a simple introduction of an ultimate enemy, because of the reference to the fresh wounds of WW2.

- System Shock. A 1993 game about a corporation's conspiracy and rogue AI trying to conquer humanity. As a freelance hacker, the player attempts to stop it. The rogue AI idea is developed further in a 1999 sequel.

So, we can see external evil forces and a heroic protagonist trying to save everyone. Not always very heroic, but it's always about resisting an external force.

Cry for Help

And what is it that S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is about? It is not about fighting a great evil, defeating or protecting anything. It's about escaping into a grim, dangerous, but free place and uncovering more secrets and atrocities committed by the same people leading outside. It's about having no trust in authority, relying only on yourself. It's about finding time between dangers to sit by the fire with fellow stalkers to sing together, eat before continuing the journey alone. And about finding beauty in the dangerous and capricious nature of the Zone. Isn't it another allusion to freedom? Ultimately, freedom, volia, is a recurring motif in many Ukrainian stories and arts.

And that's what can be a trauma response. The Soviet Union hits differently. It doesn't try just to subdue you and force you to do its bidding–it tries to dissolve you. It comes under the guise of internal force fighting for a better future, and then it tries to succumb you in, burning out all your identity and proving you asked for it. The Soviets always try to avoid being publicly convicted of being alien; they always insist on being you. While actually, they want you to become them.

It is also very similar to being boiled in a pot–they start slow, so people don't see much reason to risk it to fight it, and slowly increase the temperature, so when it becomes obvious, you are already too weak to jump.

The Soviet Union was not just conquering people; it was breaking them. And broken people can't fight; the biggest thing they can attempt is to escape.

The End

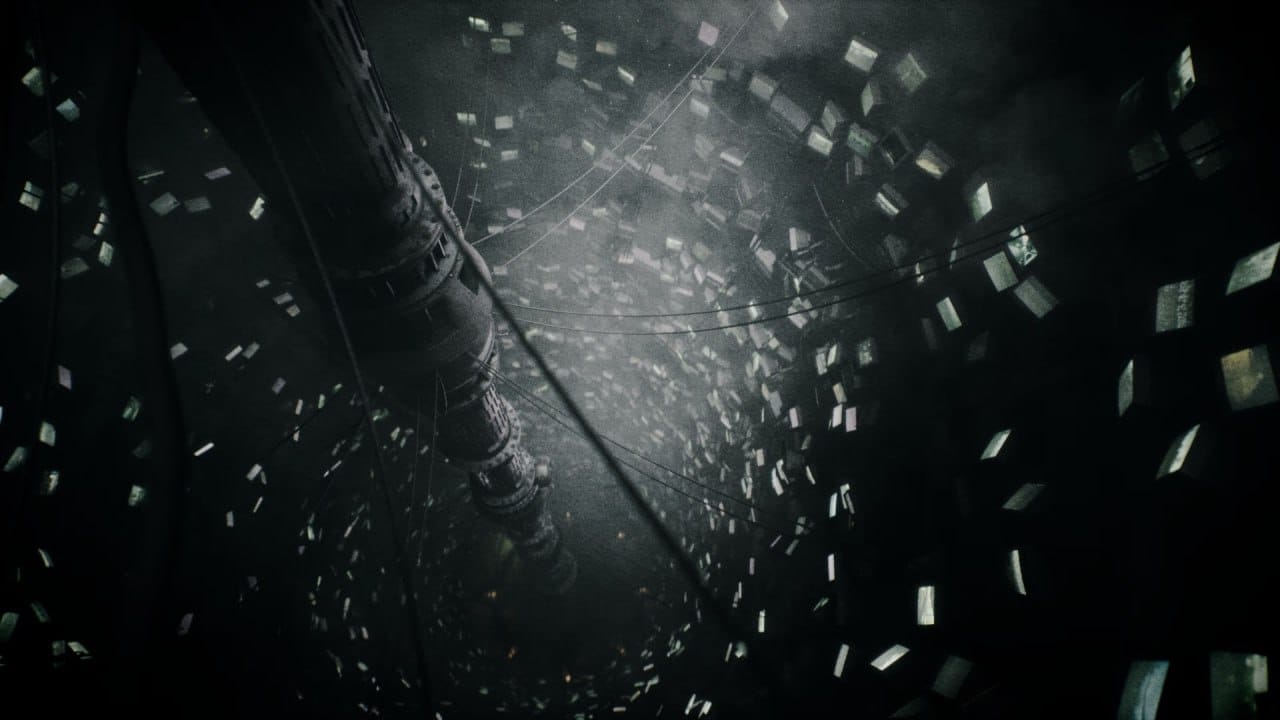

The original game's ending is very showing. You can split them into three main categories: embrace a lie, whatever you like more, join the ranks of those who see themselves above everyone else, or kill them all. And neither will actually change a thing.

The latest game preserved many of the original game's concepts and moods. Though the player feels like he has more agency, he can actually make choices that will affect the future of the Zone and the world. I will not go deeper; I will just mention that, in the best fashion of Eastern European stories, every ending will have a bitter taste.

What I do want to say is how the stalkers revere the Zone. They accept it as their new home; they protect it. And those who want to "cure" the land, whatever their motivations, they treat as enemies those who wish to take it away from them. You can watch how broken people, who left their lives outside of the Zone, found their peace among all this violence and loss, and manage to reassemble themselves from scratch, refuse to let it go.

I did wish for healing, so in my first playthrough, I tried to "cure" the zone, to bring all those people back to life. I didn't have a chance to reason with the stalkers; they basically hated me for it. But when I actually did, I felt I might have been wrong all the way. I did not save anyone; there was no one in need of me saving them. I just pushed them back into the life they tried to escape so much.

And now, with the Russian war against Ukraine, I have to watch the same evil trying to take hold of us once again. Because in Russia, they have never left. But Ukraine did. People tasted that freedom for long enough to know well what they are fighting for. So, please, support Ukraine and don't let darkness prevail.